Market: Trade Statistics, Trends

Wine (wino in Polish) production in Poland has increased more than twenty-fivefold in the last decade. Several years ago, Polish wine production was concentrated in the southern part of the country; nowadays, it is produced across the country. Poland has approximately 500 vineyards and 197 commercial wine producers making wine from local grapes. According to FAO, in 2020, Poland was the 51st largest wine producer worldwide with a total production of 11.4 thousand tons equivalent to a global production share of 0.04%.

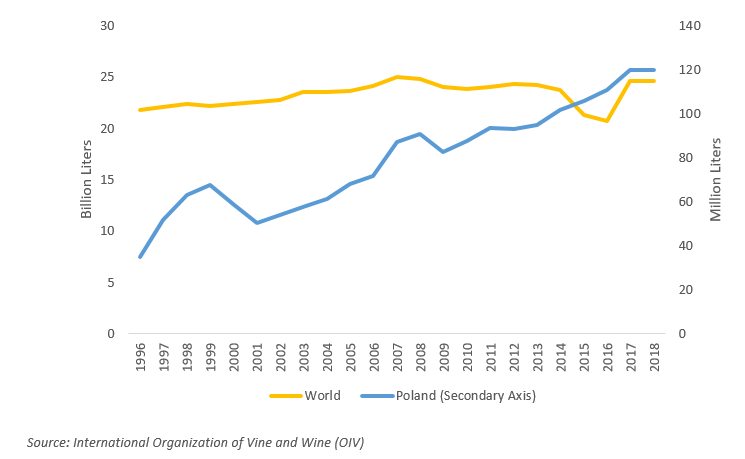

According to the International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV), in 2018, Poland was the 27th largest wine consumer, consuming around 120 million liters equivalent to a global consumption share pf 0.5%. Wine consumption grew by 20% since 2014, ten times greater than the global average. In terms of per capita consumption, in 2019, Polish people consumed an average of 0.74 liters of pure alcohol from wine, ranking as the 65th country.

In 2020, Poland ranked as the 31st largest wine exporter with a global share of 0.11%. Its wine exports grew at a much faster CAGR of 26% compared to the world average of 5% between 2001 and 2020.

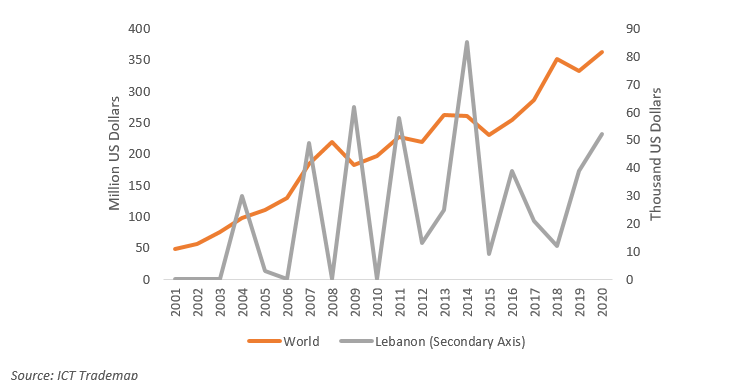

2. Import Trends Most of Poland’s wine is imported from Europe, North and South America, and Oceania, but the country also imports a small amount from African and Asian countries. Poland is a small wine importer compared to large western European countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany. However, Poland is the largest wine importer in eastern Europe (ranking as the 20th largest wine importer worldwide), with wine imports amounting to 363 million USD in 2020. By 2020, Polish wine imports grew to 7.64 times the value of 2001. In general, Polish wine imports followed a consistent upward trend with a higher-than-average increase between 2006 and 2008, in 2013 and in 2018. Slight decreases were observed in 2009, 2015 and 2019.

The value of Polish imports from Lebanon oscillated from one year to the other with a maximum value of $85,000 recorded in 2014. In 2020, wine imports from Lebanon stood at $52,000, equivalent to a share of 0.01% of total Polish wine imports, with Lebanon ranking as the 36th largest wine exporter into Poland. That same year, those Polish imports constituted 0.2% of Lebanon’s wine exports. In terms of quantity, Lebanon ranked as the 42nd largest wine supplier to Poland with only 6 tons of wine exported to Poland.

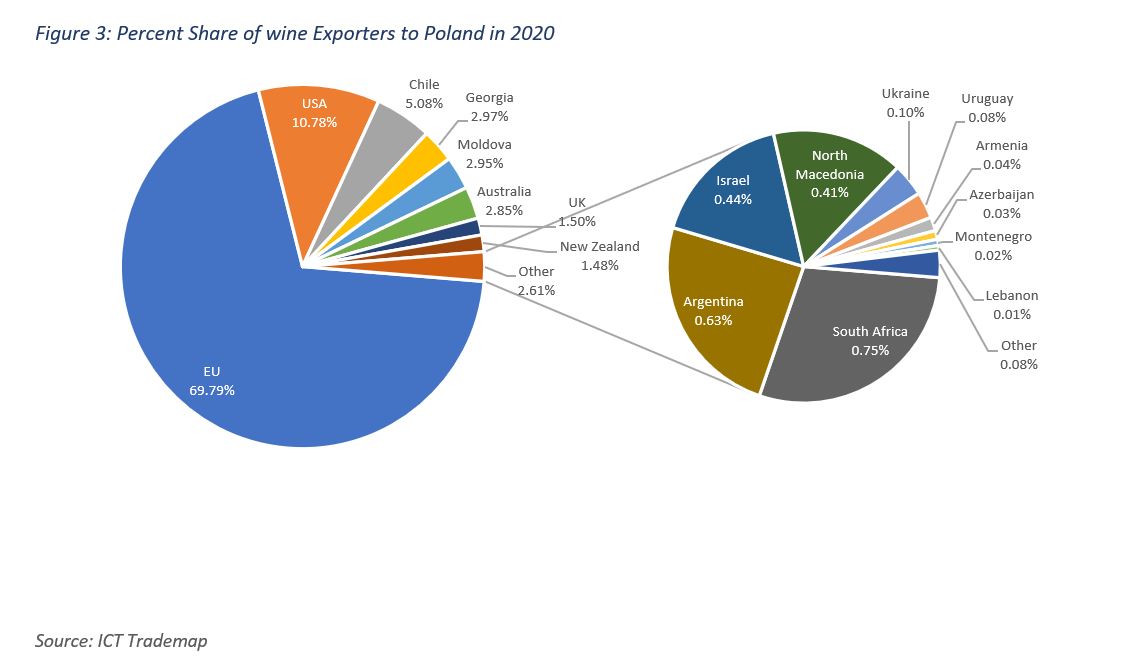

3. Market Trends In 2020, around 70% of Poland’s wine was imported from the European Union, with the biggest share from Italy (26%), followed by Germany (11%), France (11%), Spain (9%), Portugal (8%), Bulgaria (3%) and Hungary (2%). Another 2% was imported from 14 other EU countries. The United States of America was the largest non-EU wine exporter to Poland with a share of 11%, followed by Chile (5%), Georgia (3%), Moldova (3%), Australia (3%), United Kingdom (1.5%) and New Zealand (1.5%). Other supplying countries accounted for 2.7% of total Polish wine imports.

The world average imported unit value in 2020 was $2.62/liter. The average unit value of imports from Italy, France, the United States, Australia, New Zealand and Argentina exceeded the world average. The unit value of imports from Spain, Moldova, Hungary and United Kingdom were lower than the world average. While the unit value of wine imports from Bulgaria and Macedonia was less than half the world average, those from Denmark and Austria were almost double.

Meanwhile, the unit price of Polish wine imports from Lebanon was the highest at $8.67/liter. The high unit price could be a result of the high quality of wine imported from Lebanon. It could also indicate the lack of price competitiveness compared to other countries which could be hindering higher quantities of wine from being imported into Poland. Thus, a thorough study of competitive markets in terms of quality and price combined with the proper strategies of market entry could realize the growth potential of Lebanese wine exports into Poland.

4. Changes in the Polish Market For a long time, Poland was one of the least developed wine markets in Europe. Compared to the rest of Europe, wine consumption in Poland is still small. However, as wine gains popularity in Poland, the country is being perceived as a ‘growth market’. Poland is currently the 5th most attractive wine market in the world according to Wine Intelligence’s Global Compass 2020 report, up nine places from 2019. This jump in ranking can be attributed to an increasing wine drinking population and a flux of disposable income.

Although the Poles are traditionally known for their love of beer and spirits, wine sales have strongly increased since the country joined the EU in 2004 and are expected to continue to do so in the future as the country continues to experience economic growth. This could be attributed to the growing access to the product and, correspondingly, the wine drinking habit, courtesy of Poland’s wine-loving EU neighbors. Wine consumers in Poland are typically younger and more eager to discover more about wine than in other places. While the older generation of drinkers are keen to stick with what they know, maintaining that tradition of hard spirits and vodka, the younger generation are keen to break the stereotype and adopt a Western European way of alcohol consumption.

Poles generally prefer red wines followed by sweeter whites, although consumer preferences are slowly trending away from sweet wines toward drier white varietals. Sparkling wines are growing in popularity, followed by still rosés, and champagne. Sweet and semi-dry wines are particularly popular amongst a large group of elderly women.

However, the growing group of young urban professionals deem to prefer semi-dry and dry wines and to favor red wine over white or rosé wine. These young urban professionals are currently driving the development of the emerging Polish wine market. They travel a lot to other wine-consuming countries, copy drinking patterns of those countries and associate wine with Western lifestyles. Growing health-consciousness particularly stimulates the switch to wine, as moderate wine consumption is considered to be healthy. Polish regular wine drinkers have shown an increased interest and knowledge of wine categories, with an active interest in learning about the origin and in experimenting with a wider range of products.

In the past few years, knowledge about wine-producing countries and regions of origin has grown, gaining a more important role in the purchasing decisions. According to Wine Intelligence, more are now able to recall the country of origin of the wines they have consumed, compared to 3 years ago, and more are experimenting with a wider range of white and red varietals.

Although wine consumption is less seasonal than it was in the past, some seasonal trends persist. For example, sparkling wines, including champagne, are particularly popular during Christmas, New Years, Carnival in February, and during first communion season in May. The Polish wine market is dominated by low-cost table wines, but higher quality wines have made inroads among many consumers. Increasingly serious marketing efforts, on-line wine sellers, and a proliferation of wine shops, particularly in leading shopping centers, have all contributed toward popularizing higher-end wines

Despite the dominance of large retail chains and discounters over the Polish wine market, small importers and specialist retailers are on the rise. This provides opportunities for developing country exporters in both the high and low-volume segments as consumers are less prejudiced towards wine from different origins.

According to the International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV), in 2018, Poland was the 27th largest wine consumer, consuming around 120 million liters equivalent to a global consumption share pf 0.5%. Wine consumption grew by 20% since 2014, ten times greater than the global average. In terms of per capita consumption, in 2019, Polish people consumed an average of 0.74 liters of pure alcohol from wine, ranking as the 65th country.

In 2020, Poland ranked as the 31st largest wine exporter with a global share of 0.11%. Its wine exports grew at a much faster CAGR of 26% compared to the world average of 5% between 2001 and 2020.

2. Import Trends Most of Poland’s wine is imported from Europe, North and South America, and Oceania, but the country also imports a small amount from African and Asian countries. Poland is a small wine importer compared to large western European countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany. However, Poland is the largest wine importer in eastern Europe (ranking as the 20th largest wine importer worldwide), with wine imports amounting to 363 million USD in 2020. By 2020, Polish wine imports grew to 7.64 times the value of 2001. In general, Polish wine imports followed a consistent upward trend with a higher-than-average increase between 2006 and 2008, in 2013 and in 2018. Slight decreases were observed in 2009, 2015 and 2019.

The value of Polish imports from Lebanon oscillated from one year to the other with a maximum value of $85,000 recorded in 2014. In 2020, wine imports from Lebanon stood at $52,000, equivalent to a share of 0.01% of total Polish wine imports, with Lebanon ranking as the 36th largest wine exporter into Poland. That same year, those Polish imports constituted 0.2% of Lebanon’s wine exports. In terms of quantity, Lebanon ranked as the 42nd largest wine supplier to Poland with only 6 tons of wine exported to Poland.

3. Market Trends In 2020, around 70% of Poland’s wine was imported from the European Union, with the biggest share from Italy (26%), followed by Germany (11%), France (11%), Spain (9%), Portugal (8%), Bulgaria (3%) and Hungary (2%). Another 2% was imported from 14 other EU countries. The United States of America was the largest non-EU wine exporter to Poland with a share of 11%, followed by Chile (5%), Georgia (3%), Moldova (3%), Australia (3%), United Kingdom (1.5%) and New Zealand (1.5%). Other supplying countries accounted for 2.7% of total Polish wine imports.

The world average imported unit value in 2020 was $2.62/liter. The average unit value of imports from Italy, France, the United States, Australia, New Zealand and Argentina exceeded the world average. The unit value of imports from Spain, Moldova, Hungary and United Kingdom were lower than the world average. While the unit value of wine imports from Bulgaria and Macedonia was less than half the world average, those from Denmark and Austria were almost double.

Meanwhile, the unit price of Polish wine imports from Lebanon was the highest at $8.67/liter. The high unit price could be a result of the high quality of wine imported from Lebanon. It could also indicate the lack of price competitiveness compared to other countries which could be hindering higher quantities of wine from being imported into Poland. Thus, a thorough study of competitive markets in terms of quality and price combined with the proper strategies of market entry could realize the growth potential of Lebanese wine exports into Poland.

4. Changes in the Polish Market For a long time, Poland was one of the least developed wine markets in Europe. Compared to the rest of Europe, wine consumption in Poland is still small. However, as wine gains popularity in Poland, the country is being perceived as a ‘growth market’. Poland is currently the 5th most attractive wine market in the world according to Wine Intelligence’s Global Compass 2020 report, up nine places from 2019. This jump in ranking can be attributed to an increasing wine drinking population and a flux of disposable income.

Although the Poles are traditionally known for their love of beer and spirits, wine sales have strongly increased since the country joined the EU in 2004 and are expected to continue to do so in the future as the country continues to experience economic growth. This could be attributed to the growing access to the product and, correspondingly, the wine drinking habit, courtesy of Poland’s wine-loving EU neighbors. Wine consumers in Poland are typically younger and more eager to discover more about wine than in other places. While the older generation of drinkers are keen to stick with what they know, maintaining that tradition of hard spirits and vodka, the younger generation are keen to break the stereotype and adopt a Western European way of alcohol consumption.

Poles generally prefer red wines followed by sweeter whites, although consumer preferences are slowly trending away from sweet wines toward drier white varietals. Sparkling wines are growing in popularity, followed by still rosés, and champagne. Sweet and semi-dry wines are particularly popular amongst a large group of elderly women.

However, the growing group of young urban professionals deem to prefer semi-dry and dry wines and to favor red wine over white or rosé wine. These young urban professionals are currently driving the development of the emerging Polish wine market. They travel a lot to other wine-consuming countries, copy drinking patterns of those countries and associate wine with Western lifestyles. Growing health-consciousness particularly stimulates the switch to wine, as moderate wine consumption is considered to be healthy. Polish regular wine drinkers have shown an increased interest and knowledge of wine categories, with an active interest in learning about the origin and in experimenting with a wider range of products.

In the past few years, knowledge about wine-producing countries and regions of origin has grown, gaining a more important role in the purchasing decisions. According to Wine Intelligence, more are now able to recall the country of origin of the wines they have consumed, compared to 3 years ago, and more are experimenting with a wider range of white and red varietals.

Although wine consumption is less seasonal than it was in the past, some seasonal trends persist. For example, sparkling wines, including champagne, are particularly popular during Christmas, New Years, Carnival in February, and during first communion season in May. The Polish wine market is dominated by low-cost table wines, but higher quality wines have made inroads among many consumers. Increasingly serious marketing efforts, on-line wine sellers, and a proliferation of wine shops, particularly in leading shopping centers, have all contributed toward popularizing higher-end wines

Despite the dominance of large retail chains and discounters over the Polish wine market, small importers and specialist retailers are on the rise. This provides opportunities for developing country exporters in both the high and low-volume segments as consumers are less prejudiced towards wine from different origins.

Figure 1: Wine Consumption (1996 - 2018)

Figure 2: Value of Wine Imports into Poland, 2001 – 2020

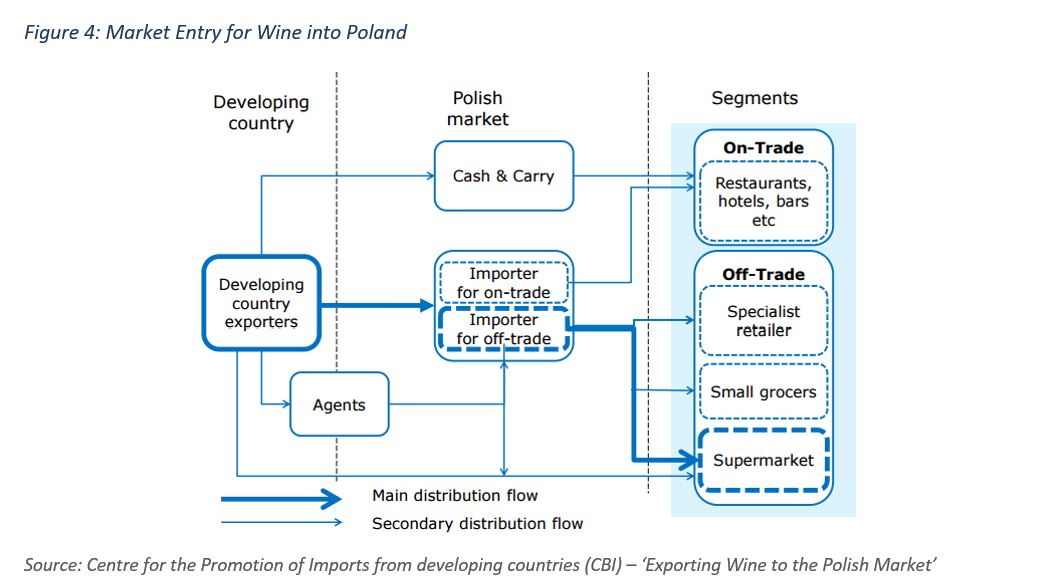

Market Entry: Trade Channels and Segments

Most Polish wine sales are made via the off-trade channel with supermarkets, hypermarkets and discounters dominating market shares. Wine continues to struggle in the on-trade, in part because it is much more expensive than other options.

Leading supermarkets are foreign-owned multinationals such as the Portuguese Biedronka, the British Tesco, and the French Carrefour and Auchan. Discounters (such as Lidl) account for a high volume of lower-priced wine sales. Major retail chains source wine directly from overseas or domestic wine suppliers to increase efficiency in distribution and reduce distribution costs, but they only sell these wines in their stores. It is expected that direct imports of hypermarkets and supermarkets increase strongly in the long term at the expense of small grocers. The profit margin in the stores is between 15% for a discounter to 30% for hyper- and supermarkets. Supermarkets in Poland charge relatively high listing fees. The payment of these fees can give suppliers access to supermarket shelves, which can be a profitable business. However, current listing fees in Poland are relatively high in comparison to the amount of sales.

Although small grocers still account for a significant share of table wine sales, they are losing market share. They are mostly supplied by importers and do not import wine directly. Their margin in the stores is approximately 15-20%.

Despite the dominance of supermarkets, hypermarkets and discounters in the Polish off-trade channel, the number of wine importers continues to grow. Wine importers focus on importing quality wine and are competitors of the large importers in that segment. They are able to provide a different kind of drinking experience compared to these large competitors. The majority of large importers distribute via their own wholesale operation or sell their products to wholesale firms, which redistribute to the appropriate channels. They supply over 50% of their wine to small grocers and the on-trade. They generally add a mark-up to cover commissions, credit risk, after-sales service and the cost of carrying a local inventory to meet small orders. Their margin generally ranges from 30-40% of the selling price, but can go down to 20% when supplying supermarkets. Examples of large players involved in trade are Ambra Group, Bartex-Bartol and CEDC.

The number of specialist retail outlets (such as wine boutiques and chains of delicatessen stores) that sell wines in the higher price segments has been growing. As knowledge on wine and demand for these segments are growing, their sales are expected to increase.

Online shops are particularly interesting retail channels for premium wines from developing countries, as they have room to provide product information, such as a story about the history of the winery. However, this channel is deemed illegal by some officials resulting in administrative hassle for internet wine shops. The online channel is currently very limited, but this could change in the future depending on how current legal issues are resolved. Winezja, Wina.pl and Marek Kondrat are example of prevailing online stores.

Developing country exporters willing to supply importers or retailers can use an agent to link them up with a trading partner. Agents are independent companies who negotiate on behalf of their clients and act as intermediaries between buyer and seller. They do not take ownership of the products, nor keep stock. Agents are starting to become again more important in the East-European markets. This development is expected to continue in the short to middle term.

The on-trade sector consists of many small players, and therefore usually does not import directly. Exporters targeting the on-trade sector can supply an importer which redirects the wine to the restaurants and other players in the Polish on-trade segment. Restaurants mostly look for wines with a reputable image and of good quality. Prices in the on-trade are relatively high, and although there is a number of high-quality restaurants which focus on fine wines, the majority of restaurant owners still do not have much interest in it.

Cash & Carries are a type of wholesaler that supplies the on-trade sector. They mostly purchase from importers and sell the wines from their warehouse where customers pay on the spot and carry the goods away themselves. In Poland, Makro is the main Cash & Carry chain.

An importer’s distribution channel will determine which wines in terms of price point and volume will be sold. It is important to ensure that the potential importer holds an import license when starting initial discussions and before sending wine samples. In addition to the import license, a distributor requires a wholesale trade and/or retail sale license. Sales volume objectives, together with the positioning of a product, will be key factors in the consideration of suitable distribution channels.

Leading supermarkets are foreign-owned multinationals such as the Portuguese Biedronka, the British Tesco, and the French Carrefour and Auchan. Discounters (such as Lidl) account for a high volume of lower-priced wine sales. Major retail chains source wine directly from overseas or domestic wine suppliers to increase efficiency in distribution and reduce distribution costs, but they only sell these wines in their stores. It is expected that direct imports of hypermarkets and supermarkets increase strongly in the long term at the expense of small grocers. The profit margin in the stores is between 15% for a discounter to 30% for hyper- and supermarkets. Supermarkets in Poland charge relatively high listing fees. The payment of these fees can give suppliers access to supermarket shelves, which can be a profitable business. However, current listing fees in Poland are relatively high in comparison to the amount of sales.

Although small grocers still account for a significant share of table wine sales, they are losing market share. They are mostly supplied by importers and do not import wine directly. Their margin in the stores is approximately 15-20%.

Despite the dominance of supermarkets, hypermarkets and discounters in the Polish off-trade channel, the number of wine importers continues to grow. Wine importers focus on importing quality wine and are competitors of the large importers in that segment. They are able to provide a different kind of drinking experience compared to these large competitors. The majority of large importers distribute via their own wholesale operation or sell their products to wholesale firms, which redistribute to the appropriate channels. They supply over 50% of their wine to small grocers and the on-trade. They generally add a mark-up to cover commissions, credit risk, after-sales service and the cost of carrying a local inventory to meet small orders. Their margin generally ranges from 30-40% of the selling price, but can go down to 20% when supplying supermarkets. Examples of large players involved in trade are Ambra Group, Bartex-Bartol and CEDC.

The number of specialist retail outlets (such as wine boutiques and chains of delicatessen stores) that sell wines in the higher price segments has been growing. As knowledge on wine and demand for these segments are growing, their sales are expected to increase.

Online shops are particularly interesting retail channels for premium wines from developing countries, as they have room to provide product information, such as a story about the history of the winery. However, this channel is deemed illegal by some officials resulting in administrative hassle for internet wine shops. The online channel is currently very limited, but this could change in the future depending on how current legal issues are resolved. Winezja, Wina.pl and Marek Kondrat are example of prevailing online stores.

Developing country exporters willing to supply importers or retailers can use an agent to link them up with a trading partner. Agents are independent companies who negotiate on behalf of their clients and act as intermediaries between buyer and seller. They do not take ownership of the products, nor keep stock. Agents are starting to become again more important in the East-European markets. This development is expected to continue in the short to middle term.

The on-trade sector consists of many small players, and therefore usually does not import directly. Exporters targeting the on-trade sector can supply an importer which redirects the wine to the restaurants and other players in the Polish on-trade segment. Restaurants mostly look for wines with a reputable image and of good quality. Prices in the on-trade are relatively high, and although there is a number of high-quality restaurants which focus on fine wines, the majority of restaurant owners still do not have much interest in it.

Cash & Carries are a type of wholesaler that supplies the on-trade sector. They mostly purchase from importers and sell the wines from their warehouse where customers pay on the spot and carry the goods away themselves. In Poland, Makro is the main Cash & Carry chain.

An importer’s distribution channel will determine which wines in terms of price point and volume will be sold. It is important to ensure that the potential importer holds an import license when starting initial discussions and before sending wine samples. In addition to the import license, a distributor requires a wholesale trade and/or retail sale license. Sales volume objectives, together with the positioning of a product, will be key factors in the consideration of suitable distribution channels.

Finding Potential Buyers

By some estimates, there are as many as 700 Polish wine importers. Beyond the leading top 50 companies, these importers tend to be small with informal operations. Only little reliable data exists for this market segment. However, Poland has several associations of wine importers and suppliers. The associations are a valuable source of information about the Polish market. Additionally, their websites include a list of their members which can be potential buyers. Members of these associations can range from small wine producers to multinational wine traders.

Stowarzyszenie Importerów i Dystrybutorów Wina or the Polish Wine Trade Association, founded in 2014 by wine industry leaders, has more than 40 members that supply a substantial share of the specialist retail and on-trade wine sales. Polska Rada Winiarstwa or the Polish Wine Council has producers, importers and distributors of wine, meads and other fermented beverages among its members. Kobiety I Wino or the Women and Wine Association is a national women’s organization in Poland with members such as importers, restaurateurs, oenologists, journalists, bloggers and wine enthusiasts.

More wine companies in Poland can be found on EUROPAGES or YP, Poland’s business directory. LinkedIn can be used to look up and contact professionals who work for companies in Poland specialized in wine. Information about wine companies in Poland can also be found on webpages specialized in exhibitions, trade fairs, F&B events and competitions such as Wine Expo Poland (annual wine trade show held in Warsaw, Poland), ENOEXPO (annual international wine fair held in Krakow, Poland), World Food Poland (annual unique food exhibition with a section for wine and spirits held in Warsaw, Poland) and Warsaw Wine Experience (annual wine event held in Warsaw, Poland).

International wine fairs are valuable platforms to develop contact base, meet buyers and build brand recognition. At these trade fairs exporters can exhibit their wine at their stand and play host for important representatives from importers, distributors and retailers from across the world. This can give them a big boost in finding interested buyers for their wine. Prowein (Düsseldorf, Germany)

is the largest annual wine trade fair for professionals from viticulture, production, trade and gastronomy. Vinexpo (Bordeaux, France) is a bi-annual wine trade fair that plays a significant role in the popularization of the wine industry and culture in Asia and Africa. Details of other wine trade shows can be found on Trade Fair Dates.

The best way to understand the Polish market is to visit and speak to local stakeholders and prepare an entry strategy for the wine product. Almost all wine buyers prefer personal meetings to emails. If contact with potential buyers is done via email, a personalized one is most suitable as generic emails are perceived as unreliable or as spam. Such emails should explain how the particular wine product adds value to the importer’s portfolio and request connection with the right contact person.

Stowarzyszenie Importerów i Dystrybutorów Wina or the Polish Wine Trade Association, founded in 2014 by wine industry leaders, has more than 40 members that supply a substantial share of the specialist retail and on-trade wine sales. Polska Rada Winiarstwa or the Polish Wine Council has producers, importers and distributors of wine, meads and other fermented beverages among its members. Kobiety I Wino or the Women and Wine Association is a national women’s organization in Poland with members such as importers, restaurateurs, oenologists, journalists, bloggers and wine enthusiasts.

More wine companies in Poland can be found on EUROPAGES or YP, Poland’s business directory. LinkedIn can be used to look up and contact professionals who work for companies in Poland specialized in wine. Information about wine companies in Poland can also be found on webpages specialized in exhibitions, trade fairs, F&B events and competitions such as Wine Expo Poland (annual wine trade show held in Warsaw, Poland), ENOEXPO (annual international wine fair held in Krakow, Poland), World Food Poland (annual unique food exhibition with a section for wine and spirits held in Warsaw, Poland) and Warsaw Wine Experience (annual wine event held in Warsaw, Poland).

International wine fairs are valuable platforms to develop contact base, meet buyers and build brand recognition. At these trade fairs exporters can exhibit their wine at their stand and play host for important representatives from importers, distributors and retailers from across the world. This can give them a big boost in finding interested buyers for their wine. Prowein (Düsseldorf, Germany)

is the largest annual wine trade fair for professionals from viticulture, production, trade and gastronomy. Vinexpo (Bordeaux, France) is a bi-annual wine trade fair that plays a significant role in the popularization of the wine industry and culture in Asia and Africa. Details of other wine trade shows can be found on Trade Fair Dates.

The best way to understand the Polish market is to visit and speak to local stakeholders and prepare an entry strategy for the wine product. Almost all wine buyers prefer personal meetings to emails. If contact with potential buyers is done via email, a personalized one is most suitable as generic emails are perceived as unreliable or as spam. Such emails should explain how the particular wine product adds value to the importer’s portfolio and request connection with the right contact person.

Export Promotional Activities

While direct alcoholic beverage promotions in hypermarkets and specialty shops are prohibited, importers and wholesalers can actively promote their products in restaurants and hotels, at wine tastings, and through professional periodicals available through subscriptions. Wine in Poland is commonly marketed through targeted trade events, where organizers work with sommeliers and selected audience.

International wine magazines are a good opportunity to promote wines and wineries. The Unique Selling Points can be communicated through an article to a wide public within the wine industry, ranging from wine experts, to wine importers and wine specialty shops. Promotion works best when unique characteristics of the region or country of production are highlighted. Branding the production origin generates interest and recognition of the wine’s region which could be used in other marketing tools. The association of wine consumption with a sophisticated and healthy lifestyle has become more important to the consumer. The most renown wine magazines in Poland are Czas Wina and Wino.

Advertisement of Alcohols, except for beers, is prohibited even online. However, social media is increasingly being used as a medium to discuss wine among wine consumers. Social media platforms offer ways to establish a personal and corporate image online and generate support for the wine brand. It provides a direct link between the seller and the customer and can be a highly effective tool for building brand awareness. A strong brand attracts more interested Polish buyers. Leveraging the website, blog and employee expertise to create a library of content that's interesting and easy to read; content that people will want to turn to for insight will build a loyal brand following. Posting consistently and creatively on social media, using live videos and resorting to influencers to promote the wine brand could have a positive effect on sales. It is important to accentuate the brand’s Unique Selling Points while using social media as well.

Additionally, wine applications such as Vivino and wine searcher , are becoming more popular among wine consumers to find a specific wine and/or to find additional information. Presenting wines in these apps helps the seller gain feedback from consumers and increases the brand’s visibility.

There is a time lag between developments in western European markets and developments in Poland. Fashion trends, such as many aromatic wines and wine cocktails, are not expected to have a significant effect on the Polish market in the near future. The time lag and the small size of the market prevent the rapid adoption of new products. Therefore, innovative packaging such as cans, PET bottles and screw caps are not very popular. Bag-in-box wine only has had some success in the on-trade.

Despite the rapid development of the Polish economy, the wine market is still far from developed. Whereas sustainability has become a niche market in western Europe, the Polish wine market is not at all concerned about sustainability. Additionally, most consumers are not aware of organic or Fairtrade wine. Check the website of Polish trade shows and exhibitions to discover the newest trends

International wine magazines are a good opportunity to promote wines and wineries. The Unique Selling Points can be communicated through an article to a wide public within the wine industry, ranging from wine experts, to wine importers and wine specialty shops. Promotion works best when unique characteristics of the region or country of production are highlighted. Branding the production origin generates interest and recognition of the wine’s region which could be used in other marketing tools. The association of wine consumption with a sophisticated and healthy lifestyle has become more important to the consumer. The most renown wine magazines in Poland are Czas Wina and Wino.

Advertisement of Alcohols, except for beers, is prohibited even online. However, social media is increasingly being used as a medium to discuss wine among wine consumers. Social media platforms offer ways to establish a personal and corporate image online and generate support for the wine brand. It provides a direct link between the seller and the customer and can be a highly effective tool for building brand awareness. A strong brand attracts more interested Polish buyers. Leveraging the website, blog and employee expertise to create a library of content that's interesting and easy to read; content that people will want to turn to for insight will build a loyal brand following. Posting consistently and creatively on social media, using live videos and resorting to influencers to promote the wine brand could have a positive effect on sales. It is important to accentuate the brand’s Unique Selling Points while using social media as well.

Additionally, wine applications such as Vivino and wine searcher , are becoming more popular among wine consumers to find a specific wine and/or to find additional information. Presenting wines in these apps helps the seller gain feedback from consumers and increases the brand’s visibility.

There is a time lag between developments in western European markets and developments in Poland. Fashion trends, such as many aromatic wines and wine cocktails, are not expected to have a significant effect on the Polish market in the near future. The time lag and the small size of the market prevent the rapid adoption of new products. Therefore, innovative packaging such as cans, PET bottles and screw caps are not very popular. Bag-in-box wine only has had some success in the on-trade.

Despite the rapid development of the Polish economy, the wine market is still far from developed. Whereas sustainability has become a niche market in western Europe, the Polish wine market is not at all concerned about sustainability. Additionally, most consumers are not aware of organic or Fairtrade wine. Check the website of Polish trade shows and exhibitions to discover the newest trends

Doing Business: Business Culture

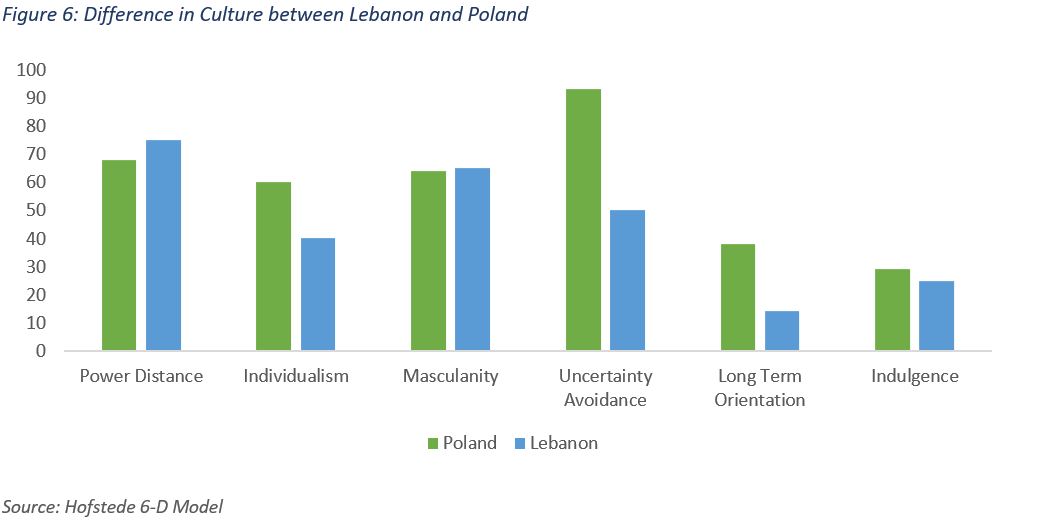

Culture is defined as the collective attitudes and behavior which distinguishes one group of people from another. It is the patterns of thinking which are reflected in the meaning people attach to various aspects of life and which become crystallized in the institutions of a society. However, this does not mean that everyone in a given society is programmed in the same way.

Power Distance : the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally.

Both Lebanon and Poland score high on power distance indicating that both follow a hierarchal and centralized system with subordinates expecting clear directions from their autocratic managers.

Individualism: the degree of interdependence a society maintains among its members.

While Lebanon scores low on individualism reflecting its collectivistic society, Poland scores high indicating its loosely-knit social framework. The former perceives employer/ employee relationships in moral terms and the latter defines it in a contract.

Poland scores high on both power distance and individualism emphasizing the importance of everyone in the system despite their inequality.

Power Masculinity : whether society is driven by competition, achievement and success (masculine) or dominant values in society are caring for others and quality of life (feminine).

Both Lebanon and Poland score high on masculinity indicating their masculine societies. Managers in both countries are expected to be decisive and assertive. There is a lot of emphasis on equity, competition and performance.

Uncertain Avoidance : the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations and have created beliefs and institutions that try to avoid these.

Lebanon scored midway and thus, shows no clear preference. Poland, however, is among the uncertainty avoidant countries with a strong preference for rigid codes of belief and behavior. Poles have a strong urge for hard-work, precision and punctuality. Innovation is resisted while security is an important element in individual motivation.

Long Term Orientation: how every society has to maintain some links with its own past while dealing with the challenges of the present and future.

Both Lebanon and Poland score low on long-term orientation indicating normative rather than pragmatic societies. People in both societies exhibit great respect for traditions, a relatively small propensity to save for the future, and a focus on achieving quick results.

Indulgence: the extent to which people try to control their desires and impulses.

Both countries score low on this dimension indicating that both cultures are rather restrained in nature. Such societies have a tendency to cynicism and pessimism. They have the perception that their actions are restrained by social norms and that self-indulgence is wrong. Restrained societies do not put much emphasis on leisure time and control the gratification of their desires.

Establishing personal rapport is important when conducting business in Poland and most purchases are made after in-person meetings. English is often used as the language of international commerce, but translation services may also be necessary.

According to Cultural Atlas, it is customary for businesspeople to shake hands upon meeting while maintaining direct eye contact. Professional contacts should be initially addressed as Pan (Mr.) or Pani (Mrs.) followed by their surname. People with professional positions are addressed by their job as their title (for example: “Pan Inzynier” (Mr Engineer), “Pani Profesor” (Ms Professor)). People usually shake women’s hands first before addressing any men present and greet older women before girls.

Business cards are the norm and are generally given to each person at a meeting. Standard business attire is recommended, including a jacket and tie for men and a suit or dress for women. Jaywalking, drinking in public places and smoking in non-designated areas are all generally frowned upon.

Generally, Poles like to build personal relationships with those they do business with and get to know people’s personalities. While people interact quite formally, there is a lot of ‘professional closeness’. It can be wise to keep a healthy distance in business friendships as close relationships can often entail favors in the workplace later on.

Poles tend to have quite a discerning eye for fairness. They request hard facts and projections and do not appreciate boasting and broad claims. They look for honest commitments to the process and quality of relations and not mere focus on the short-term outcome. They tend to have tolerance for imprecision but not so much for lateness. In general, they are not prompt in telephone and email responses and might resort to out-of-office-hours phone calls.

Power Distance : the extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally.

Both Lebanon and Poland score high on power distance indicating that both follow a hierarchal and centralized system with subordinates expecting clear directions from their autocratic managers.

Individualism: the degree of interdependence a society maintains among its members.

While Lebanon scores low on individualism reflecting its collectivistic society, Poland scores high indicating its loosely-knit social framework. The former perceives employer/ employee relationships in moral terms and the latter defines it in a contract.

Poland scores high on both power distance and individualism emphasizing the importance of everyone in the system despite their inequality.

Power Masculinity : whether society is driven by competition, achievement and success (masculine) or dominant values in society are caring for others and quality of life (feminine).

Both Lebanon and Poland score high on masculinity indicating their masculine societies. Managers in both countries are expected to be decisive and assertive. There is a lot of emphasis on equity, competition and performance.

Uncertain Avoidance : the extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations and have created beliefs and institutions that try to avoid these.

Lebanon scored midway and thus, shows no clear preference. Poland, however, is among the uncertainty avoidant countries with a strong preference for rigid codes of belief and behavior. Poles have a strong urge for hard-work, precision and punctuality. Innovation is resisted while security is an important element in individual motivation.

Long Term Orientation: how every society has to maintain some links with its own past while dealing with the challenges of the present and future.

Both Lebanon and Poland score low on long-term orientation indicating normative rather than pragmatic societies. People in both societies exhibit great respect for traditions, a relatively small propensity to save for the future, and a focus on achieving quick results.

Indulgence: the extent to which people try to control their desires and impulses.

Both countries score low on this dimension indicating that both cultures are rather restrained in nature. Such societies have a tendency to cynicism and pessimism. They have the perception that their actions are restrained by social norms and that self-indulgence is wrong. Restrained societies do not put much emphasis on leisure time and control the gratification of their desires.

Establishing personal rapport is important when conducting business in Poland and most purchases are made after in-person meetings. English is often used as the language of international commerce, but translation services may also be necessary.

According to Cultural Atlas, it is customary for businesspeople to shake hands upon meeting while maintaining direct eye contact. Professional contacts should be initially addressed as Pan (Mr.) or Pani (Mrs.) followed by their surname. People with professional positions are addressed by their job as their title (for example: “Pan Inzynier” (Mr Engineer), “Pani Profesor” (Ms Professor)). People usually shake women’s hands first before addressing any men present and greet older women before girls.

Business cards are the norm and are generally given to each person at a meeting. Standard business attire is recommended, including a jacket and tie for men and a suit or dress for women. Jaywalking, drinking in public places and smoking in non-designated areas are all generally frowned upon.

Generally, Poles like to build personal relationships with those they do business with and get to know people’s personalities. While people interact quite formally, there is a lot of ‘professional closeness’. It can be wise to keep a healthy distance in business friendships as close relationships can often entail favors in the workplace later on.

Poles tend to have quite a discerning eye for fairness. They request hard facts and projections and do not appreciate boasting and broad claims. They look for honest commitments to the process and quality of relations and not mere focus on the short-term outcome. They tend to have tolerance for imprecision but not so much for lateness. In general, they are not prompt in telephone and email responses and might resort to out-of-office-hours phone calls.

Tips

- Develop a Unique Selling Point, such as unusual origins, varieties, wine show medals, a Geographical Indication, and production or region stories to gain access to wine importers.

- Although direct sales are growing, importers are likely to be your best market entry point in Poland since you will be able to profit from sales growth in supermarkets and specialist retailers. Importers are also able to meet the strict logistical requirements of retail chains, such as short-notice deliveries. Only target supermarkets directly if you have significant experience in exports and are able to guarantee high volumes at a low price.

- Use the membership lists of wine associations to find potential buyers and source important information on the Polish market players.

- If you participate as a visitor at a trade fair, make sure to identify your potential buyers beforehand and thoroughly study their websites to understand their needs and wishes. Visit their exhibition stand, introduce your company and establish initial contact. Make sure that you can explain to them in no more than two minutes why they should buy your wine and in what ways you constitute an interesting business partner

- Keep in mind that it is costly to participate as an exhibitor at a trade fair. Find other wine producers/brand owners in your country and team up for a country pavilion. This way you can share the costs of an exhibition stand and make a greater impression at the trade fair.

- Remember that importers look for wine exporters who want to establish a long-term presence in the market and are not only looking to make a quick sale. Emphasize that you are keen to build sales and brand awareness in partnership with the importer.

- Participate in wine tasting events to gain recognition for your wine which you can use for marketing purposes.

- Use traditional packaging (i.e. classic bottle, labelling and cork) for promotion as they are preferred by the Polish consumer. Look for trends in western European market, providing a preview of new trends that might be adopted by the Polish wine market.

- Do not invest in organic or Fairtrade certification. The demand is very low in Poland. Instead, focus on cost reduction or branding of your product to position it as a sophisticated product.

- Aim for long-term contracts and stable trade relationships to prevent your buyer from switching to a new entrant.